Hello.

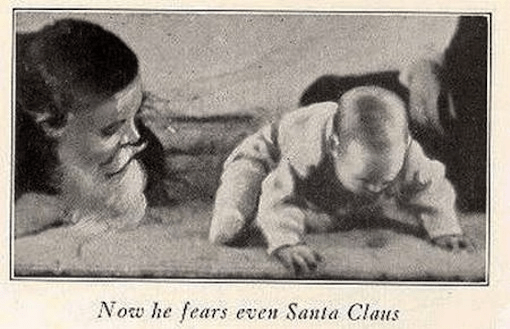

I was taking some notes on a famous psychological experiment known simply as the “Little Albert” experiment. In it, a baby was subjected to loud noises whenever it saw a white rat. After a while, the baby began to cry and fear not just white rats, but furry objects in general even without the noises. The true identity of Little Albert is still unclear, though Douglas Merritte, who died at the age of six from hydrocephalus, is usually brought up as the most likely. This is just one example of a history of psychological experiments pairing profound discoveries with ethical issues. The Little Albert experiment did shine a lot of light onto research in unconditioned and conditioned responses. However, moral issues caused a change in how psychological experiments are held today and in the future.

LEGACIES

Mostly in its formative years, psychology has had many experiments that would be considered completely impossible today. A couple of examples, outside of Little Albert, include:

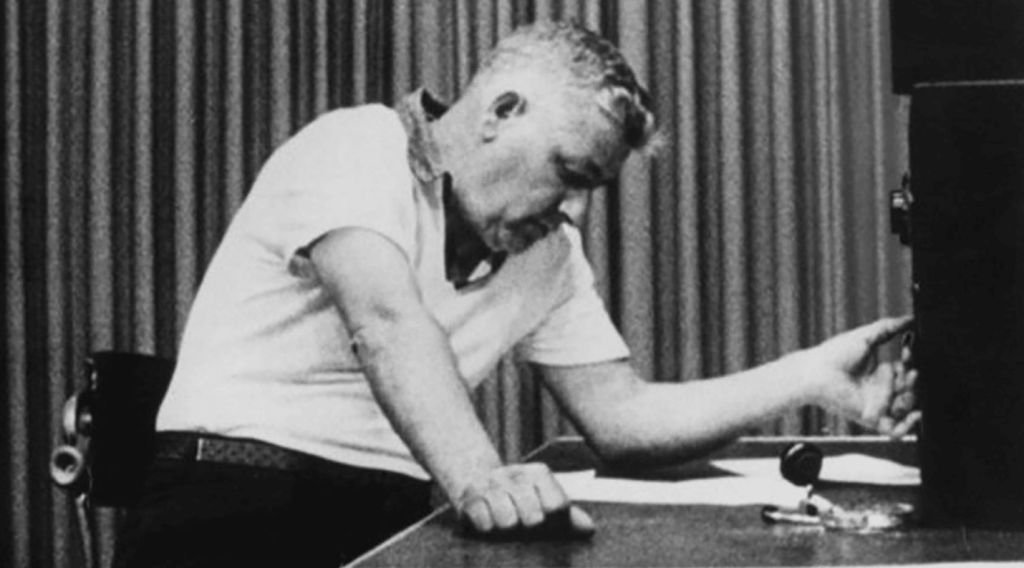

The Milgram Experiment, in which Stanley Milgram asked participants to give what they were told were electric shocks to others. Surprisingly, results showed that 65% of participants obeyed orders and gave shocks of the highest voltage, even after hearing cries of pain. Similarly to Little Albert, there was useful information gained from this: the power of authority. However, participants were left distressed and questioning their own morality.

Another is the Stanford Prison Experiment. Phillip Zimbardo’s study involved giving roles of “prisoners” or “guards” to male students, with guards being instructed to prevent prisoners from e scaping. However, the prisoners began to get abused psychologically by the “guards”, causing Zimbardo to end the experiment on the sixth day after participants had troubling mental evaluations. The study exposed the dark sides of human behavior but faced heavy backlash for its obvious oversights.

It was in part due to these controversies in the past that today there are multiple safeguards in psychological research. For example, informed consent requires participants to be fully aware of a study’s purpose, risks, and benefits before they can agree to take part in the experiment. Researchers are also obligated to prioritize the well-being of participants, avoiding physical or psychological distress whenever possible. Finally, confidentiality protects the person data of participants and creates more trust in research practices.

These rules are available in guidelines like the Belmont Report and the APA’s Code of Ethics. The idea is to balance the pursuit of knowledge with respect for human dignity in all experiments.

GRAY AREA

I wouldn’t be talking about this if there weren’t still ethical problems in modern psychology. One of the hardest issues to approach is deception. Deception involves withholding information about a study’s true purpose. There’s a reason this is necessary – sometimes participants will answer questions in ways that make them look better, or use the purpose of the search to skew the way they answer. Because of this, its often necessary for some level of deception to be used in experiments. As seen in the Milgran Experiment, though, there are moral issues with deception. Researchers today must make sure its both justified and that participants are debriefed on what happened immediately afterwards.

There must also be a right to withdraw – participants need to be able to exit the study at any time without facing penalty. Before experiments are started, IRBs or similar committees now review proposed studies to evaluate ethical implications.

Another issue revolves around “dual relationships”, occurring when a psychologist has multiple roles with a client or participant, such as being both a therapist and a friend. Dual relationships aren’t strictly unethical, but they can blur the lines of objectivity and power dynamics, potentially leading to exploitation or biased decision-making. Clear professional boundaries – these are key to avoiding issues. If personal interests or emotional involvement at any point interfere with studies, they must be avoided at all times.

To a lesser extent, issues regarding studies spanning multiple cultures can sometimes cause Western biases, which challenge the universality of findings. Inequitable outcomes for marginalized groups are the most common result of bias, notable because one of the key components of psychology is empirical evidence to back up claims. When biases occur and potentially change that, it’s important to resolve and prevent those issues as fast as possible.

ULTIMATE GOALS

Technology has been increasingly used in therapy and research, raising new ethical concerns. For example, the confidentiality of digital communication, the potential for miscommunication, and the possibility of exploiting vulnerable populations are new, unique challenges for ethical practice. It’s critical to understand that we can’t just rely on what’s been done in the past. As we move forwards, new issues will arise that we have not encountered before. Keeping up with the times and training with digital tools is necessary to preserve the standards that are now in place.

Psychology will only continue to evolve further into the future. In turn, so will ethical concerns, requiring constant vigilance tot ensure practitioners and researchers adhere to standards of conduct. In the end, it’s important to make the distinction that human welfare is more important than scientific discovery. When searching for new information it must never come at the cost of humanity. The lessons taught to us by the formerly mentioned experiments must remain clear when attempting to move further into research of the mind. The ethically of psychological experiments isn’t quite a static goal, but more so a dynamic responsibility. We can continue to question, refine, and adapt our practices, but while doing so we must ensure that the pursuit of knowledge is both enlightening and humane.

Leave a comment